The Night the Sky Was Ablaze

In the middle of the night on September 2, 1859, gold miners living in tents in Colorado were wakened by bright lights in the sky. They rose and began making breakfast, thinking it was morning. Even birds and other animals believed that the morning had come. A New Orleans paper reported that three unfortunate larks, which normally don’t emerge from their nests until morning, were shot in the middle of the night. In London, England, the lights were even bright enough to cast a shadow on the ground. People who were up late that night in the northeastern states of the USA could read books and newspapers with just the lights in the sky. They watched the eerie colorful lights dance in the northern sky with wonder and awe. 1

In the eastern and southern United States, the sky was blood red. Many citizens believed that the sky or neighboring towns were on fire. In some areas, fire trucks were even sent to help put out the huge inferno. Some people were filled with fear and dread. They thought the lights were an omen of bad things to come, like an epidemic, a revolution, or even the end of the world. Others were familiar with the Northern Lights, or Aurora Borealis as scientists call them, but wondered why they were appearing so far south. Normally, they appeared only over the far northern latitudes. However, on this night and for several nights thereafter, the lights could be seen as far south as Hawaii and the Bahamas. 1

In the eastern and southern United States, the sky was blood red. Many citizens believed that the sky or neighboring towns were on fire. In some areas, fire trucks were even sent to help put out the huge inferno. Some people were filled with fear and dread. They thought the lights were an omen of bad things to come, like an epidemic, a revolution, or even the end of the world. Others were familiar with the Northern Lights, or Aurora Borealis as scientists call them, but wondered why they were appearing so far south. Normally, they appeared only over the far northern latitudes. However, on this night and for several nights thereafter, the lights could be seen as far south as Hawaii and the Bahamas. 1

Other Strange Occurrences

The lights weren’t the only strange things to have happened that week. On the night of August 28th, telegraph wires suddenly began throwing sparks, shocking several operators. Four days later it happened again, this time causing even more damage. Some of the batteries that ran the telegraph machines exploded, so all had to be disconnected. The operators then discovered something incredible: messages could still be transmitted for several hours without their power supply. The electric currents flowing through the lines were so powerful at times that the platinum contacts were in danger of melting. Streams of fire came through the circuits and some telegraph paper caught fire. One telegraph operator was severely shocked when his forehead accidentally touched a ground wire. 2 Even simple magnetic compasses went haywire for several hours. 3

In 1859, not much was known about the cause of all these strange occurrences. While scientists and educated people knew about auroras, they did not know what caused them. People who worked for the telegraph companies had seen a connection between the appearance of auroras in the sky and interference in the lines in the past. However, it had never caused this many problems. There were many theories presented to explain the strange occurrences. Some thought that volcanic eruptions or earthquakes caused them. Others wondered if they were connected somehow to icebergs. Still others thought it was the friction caused by the earth plunging through space vapor that made the vapor turn luminous.1

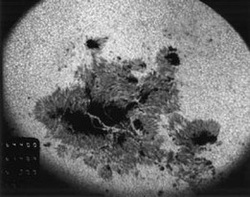

One astronomer, named Richard Carrington, had been watching a large group of sunspots on the surface of the sun that week. On the morning of September 1st, 1859, he noticed that two brilliant white lights appeared over the sunspots. They became more intense for a few minutes and then disappeared altogether. He recorded in his journal all the observations, along with drawings of what he had seen. As the aurora lit the night sky and telegraph wires malfunctioned the next day, Carrington made an important deduction. He reasoned that the bright spots, or solar flares, that he had seen on the sun’s surface the day before were somehow connected to those events. 2

The lights weren’t the only strange things to have happened that week. On the night of August 28th, telegraph wires suddenly began throwing sparks, shocking several operators. Four days later it happened again, this time causing even more damage. Some of the batteries that ran the telegraph machines exploded, so all had to be disconnected. The operators then discovered something incredible: messages could still be transmitted for several hours without their power supply. The electric currents flowing through the lines were so powerful at times that the platinum contacts were in danger of melting. Streams of fire came through the circuits and some telegraph paper caught fire. One telegraph operator was severely shocked when his forehead accidentally touched a ground wire. 2 Even simple magnetic compasses went haywire for several hours. 3

In 1859, not much was known about the cause of all these strange occurrences. While scientists and educated people knew about auroras, they did not know what caused them. People who worked for the telegraph companies had seen a connection between the appearance of auroras in the sky and interference in the lines in the past. However, it had never caused this many problems. There were many theories presented to explain the strange occurrences. Some thought that volcanic eruptions or earthquakes caused them. Others wondered if they were connected somehow to icebergs. Still others thought it was the friction caused by the earth plunging through space vapor that made the vapor turn luminous.1

One astronomer, named Richard Carrington, had been watching a large group of sunspots on the surface of the sun that week. On the morning of September 1st, 1859, he noticed that two brilliant white lights appeared over the sunspots. They became more intense for a few minutes and then disappeared altogether. He recorded in his journal all the observations, along with drawings of what he had seen. As the aurora lit the night sky and telegraph wires malfunctioned the next day, Carrington made an important deduction. He reasoned that the bright spots, or solar flares, that he had seen on the sun’s surface the day before were somehow connected to those events. 2

What Scientists Know Now

Nowadays scientists know that Carrington was correct to assume that the solar flares had caused the auroras and chaos in the telegraph systems. What Carrington saw were rare white light solar flares and he was one of the first scientists ever to observe and record any. These solar flares are capable of ejecting a massive burst of plasma, a chunk of the sun’s surface, into space. This burst of plasma is called a coronal mass ejection (CME). The CME that Carrington recorded had the energy of ten billion atomic bombs. It was so powerful, it traveled to the earth within just fifteen hours. 2

Usually, CMEs from the sun are not directed at earth. Occasionally they are, but they are normally deflected by the earth’s magnetic field. The CME of August 28th, 1859 likely weakened the magnetic field when it hit the earth. When the CME of September 1st struck, it was powerful enough to collapse the earth’s weakened magnetic field and send a surge of electrically charged particles around the globe. Scientists call this a geomagnetic storm. The geomagnetic storm of the Carrington Event caused the enormous electric surges on the telegraph lines and also caused the auroras. The electric currents of a geomagnetic storm agitate the atoms in earth’s upper atmosphere, making them glow, much like neon lights. Normally these auroras can only be seen near the north and south poles. Very large and intense geomagnetic storms cause the auroras to appear farther away from the poles. 4

Scientists now know that CMEs hit the earth from time to time, but there has not been one as big as the Carrington Event for more than 500 years. They speculate that when the next big CME comes, it will likely cause much more damage to civilization. This is because we are so reliant on technology that is vulnerable to geomagnetic storms, such as power grids, satellites, GPS, and computers. 4

Sources:

1. http://www.solarstorms.org/

2. http://www.history.com/news/a-perfect-solar-superstorm-the-1859-carrington-event

3. http://www.csmonitor.com/Science/Cool-Astronomy/2010/0809/Could-a-solar-storm- send-us-back-to-the-Stone-Age

4. http://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2008/06may_carringtonflare/

Nowadays scientists know that Carrington was correct to assume that the solar flares had caused the auroras and chaos in the telegraph systems. What Carrington saw were rare white light solar flares and he was one of the first scientists ever to observe and record any. These solar flares are capable of ejecting a massive burst of plasma, a chunk of the sun’s surface, into space. This burst of plasma is called a coronal mass ejection (CME). The CME that Carrington recorded had the energy of ten billion atomic bombs. It was so powerful, it traveled to the earth within just fifteen hours. 2

Usually, CMEs from the sun are not directed at earth. Occasionally they are, but they are normally deflected by the earth’s magnetic field. The CME of August 28th, 1859 likely weakened the magnetic field when it hit the earth. When the CME of September 1st struck, it was powerful enough to collapse the earth’s weakened magnetic field and send a surge of electrically charged particles around the globe. Scientists call this a geomagnetic storm. The geomagnetic storm of the Carrington Event caused the enormous electric surges on the telegraph lines and also caused the auroras. The electric currents of a geomagnetic storm agitate the atoms in earth’s upper atmosphere, making them glow, much like neon lights. Normally these auroras can only be seen near the north and south poles. Very large and intense geomagnetic storms cause the auroras to appear farther away from the poles. 4

Scientists now know that CMEs hit the earth from time to time, but there has not been one as big as the Carrington Event for more than 500 years. They speculate that when the next big CME comes, it will likely cause much more damage to civilization. This is because we are so reliant on technology that is vulnerable to geomagnetic storms, such as power grids, satellites, GPS, and computers. 4

Sources:

1. http://www.solarstorms.org/

2. http://www.history.com/news/a-perfect-solar-superstorm-the-1859-carrington-event

3. http://www.csmonitor.com/Science/Cool-Astronomy/2010/0809/Could-a-solar-storm- send-us-back-to-the-Stone-Age

4. http://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2008/06may_carringtonflare/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed